Cross Architecture

Alessandro Meo - Nov. 10, 2020

The Cross Architecture is a SW architecture approach inspired by the combination of some well-known design techniques, like the multi-layer architecture, the Onion Architecture, the Clean Architecture and the DDD.

The main idea that led me to the definition of the Cross Architecture was to describe a flexible way for designing the architecture of a SW over the actual application needs, while respecting a set of basic constraints providing good decoupling, testability and logical organization of code. Also, the same set of rules should provide a guidance for extending the architecture in order to follow potential application evolutions.

In practice, the above set of rules should be able to span and serve to rather different situations, hence the name Cross Architecture.

Example Solutions

For supporting the Cross Architecture approach, some example solutions have been made available for download:

General Concepts

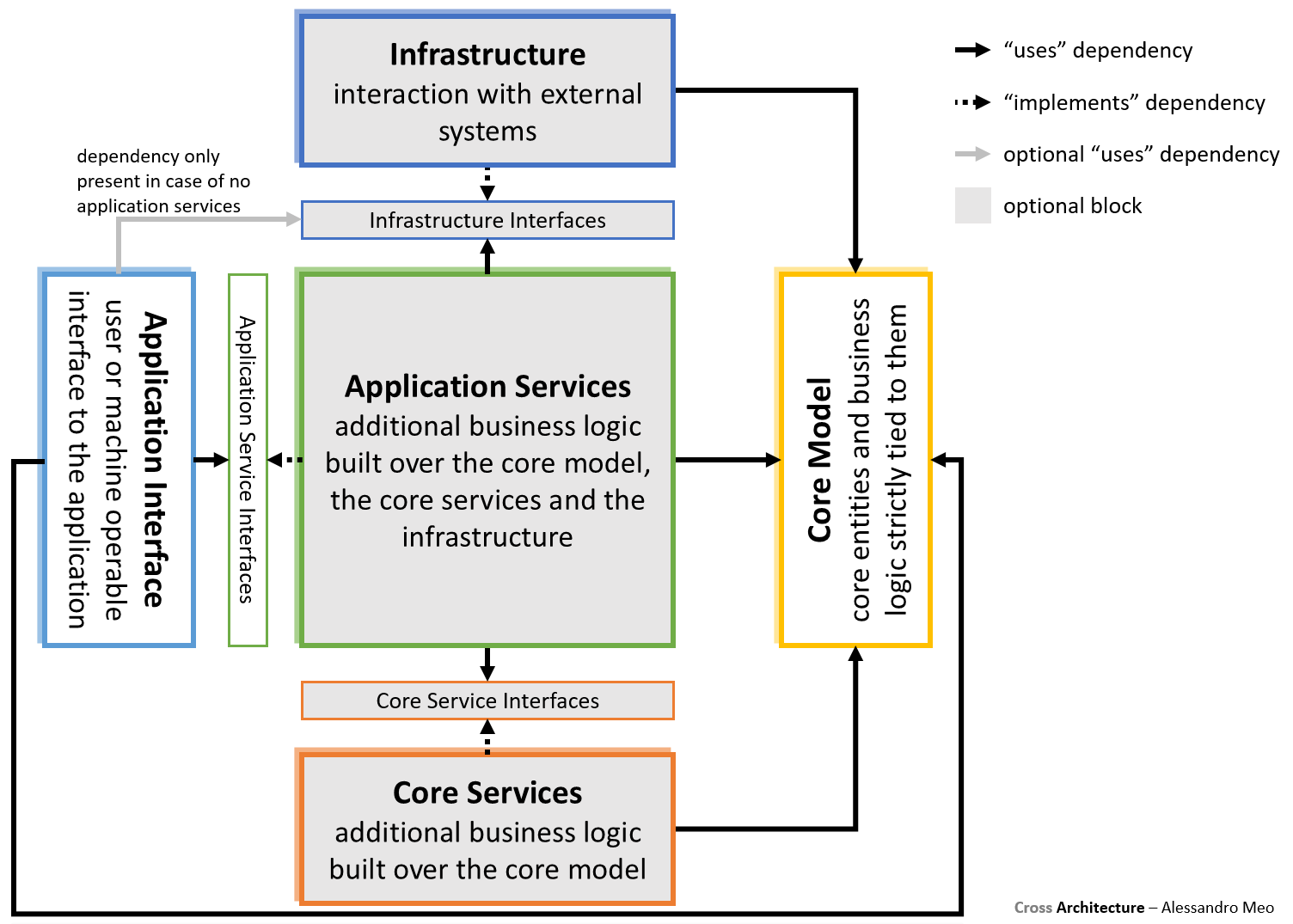

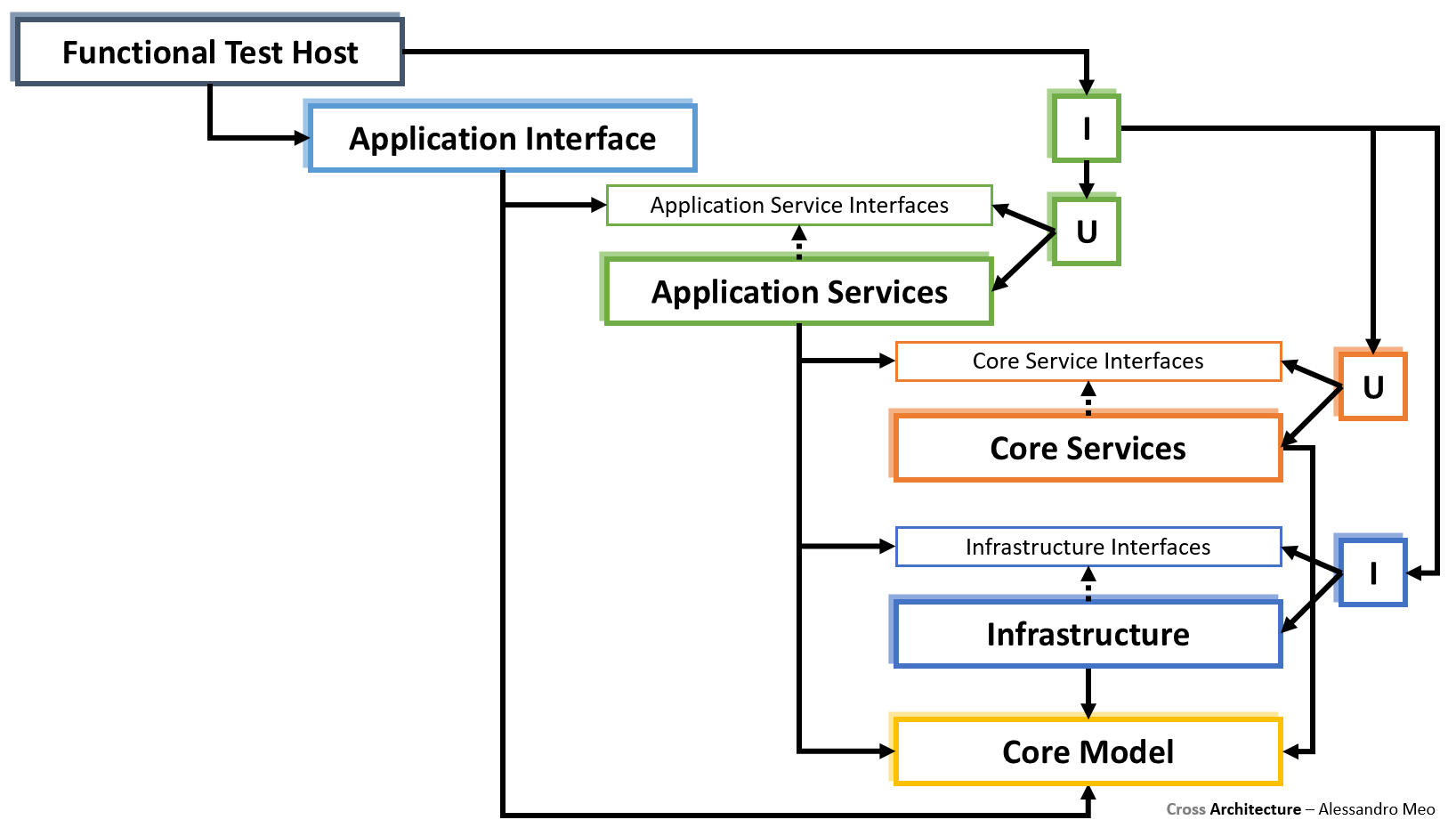

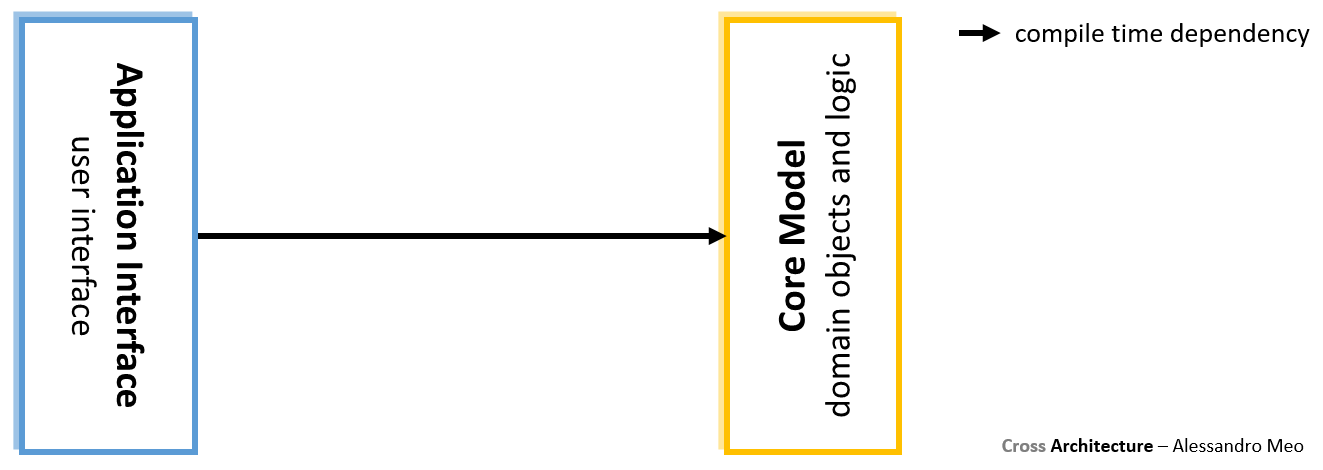

The Cross Architecture can be represented by the following cross-shaped schema.

Each box in the schema represents a Logical Area that may be implemented by one or more SW blocks (either unrelated or organized in loosely coupled layers) or even by no SW block in case the Logical Area is marked as optional (gray background).

The compile time dependencies between the SW blocks are explicitly expressed, together with their intended use, by means of arrows among the holding boxes:

- a “uses” dependency means that the dependent block uses the pointed one, moreover, in case the pointed block is an interface block (i.e.: a block abstraction), one of its implementations is required to be injected into the dependent block; more precisely, this is about the contained classes. (Note that in Application Interface the term “interface” does not make reference to a block abstraction);

- an “implements” dependency means that the dependent block implements the pointed one; more precisely, this is about the contained classes.

All the interface blocks (block abstractions) depend on the Core Model, but, for sake of simplicity, these dependencies have not been represented in the schemas of this article.

The dependency between the Application Interface and the Infrastructure Interfaces logical areas is only present when no SW block implements the Application Services logical area.

Logical Areas

The Logical Areas provided by the Cross Architecture are the following ones:

-

Core Model: core entities and business logic strictly tied to them. Depending on the situation, it may contain a DDD domain model, a set of plain old objects representing the model or anything in between; in any case, the Core Model should always be present and contain a model of the business being implemented. The business logic contained in the Core Model, if any, should be strictly tied to concepts represented by the core entities; additional logics, for example built over the interaction between entities, should be implemented in the Core Services or in the Application Services.

-

Core Service Interfaces: interfaces for the Core Services logical area.

-

Core Services: additional business logic built over the Core Model. This is an optional Logical Area, typically involved in complex situations when a separation of the business logic into different layers is required; the business logic implemented in the Core Services are typically related to more than one core entity and cannot interact with external systems (no injection of the Infrastructure into the Core Services should be present). No Core Services can be present without some Application Services.

-

Application Service Interfaces: interfaces for the Application Services logical area.

-

Application Services: additional business logic built over the Core Model, the Core Services and the Infrastructure. This is an optional Logical Area, typically involved in situations with medium-to-high complexity; the Application Services contain business logic typically related to the orchestration of core entities, Business Services (if present) and Infrastructure (if present), but, depending on the situation, they may also integrate business logic more strictly tied to sets of core entities (when no Business Services are present) or even to single core entities (in case of dry Core Model). When present, the Application Services are the only entry point the Application Interface can use for employing the Core Services or Infrastructure features.

-

Infrastructure Interfaces: interfaces for the Infrastructure logical area.

-

Infrastructure: interaction with external systems. This is an optional Logical Area typically implementing interaction with databases, mail servers, file storages and service based external applications.

-

Application Interface: user or machine operable interface to the application. This is a mandatory Logical Area providing the operable entry point to the application for users or client systems; this is not necessarily dedicated to human users, but, for example, may also be implemented as a web API or service application.

Composition Chain

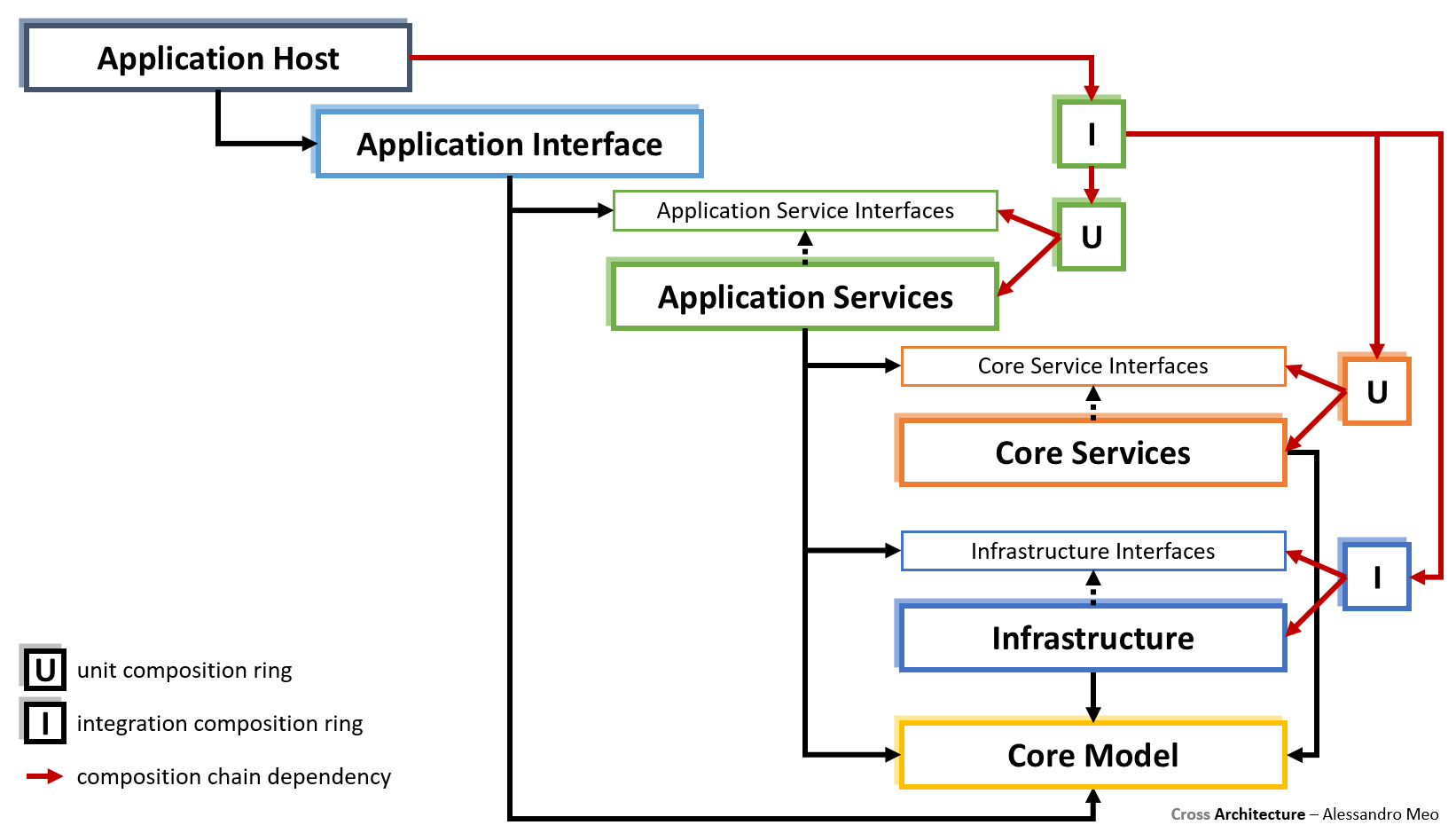

The Logical Areas described in the previous section only deals with loosely coupled SW block sets implementing the application features, but, in order to complete the actual SW, the composition root code should be added.

For keeping a high level of flexibility, in the Cross Architecture the composition root code is split into several blocks called Unit Composition Rings and Integration Composition Rings (the ones holding the “U” and “I” letters in the schema); the Composition Rings get then chained together in a nested reference tree called Composition Chain.

The difference between Unit Composition Rings and Integration Composition Rings is that the former contain the composition code providing isolated SW units, while the latter contain the composition code providing integration of SW blocks with other SW blocks or external systems.

As shown above, the Composition Chain is rooted in the Application Host, whose responsibility is to build the SW layer stack and provide any configuration or action required for the application startup. The Application Host is the actual SW application entry point, built as a ready-to-run executable or potentially hosted inside an application server (e.g.: an HTTP server).

Testing

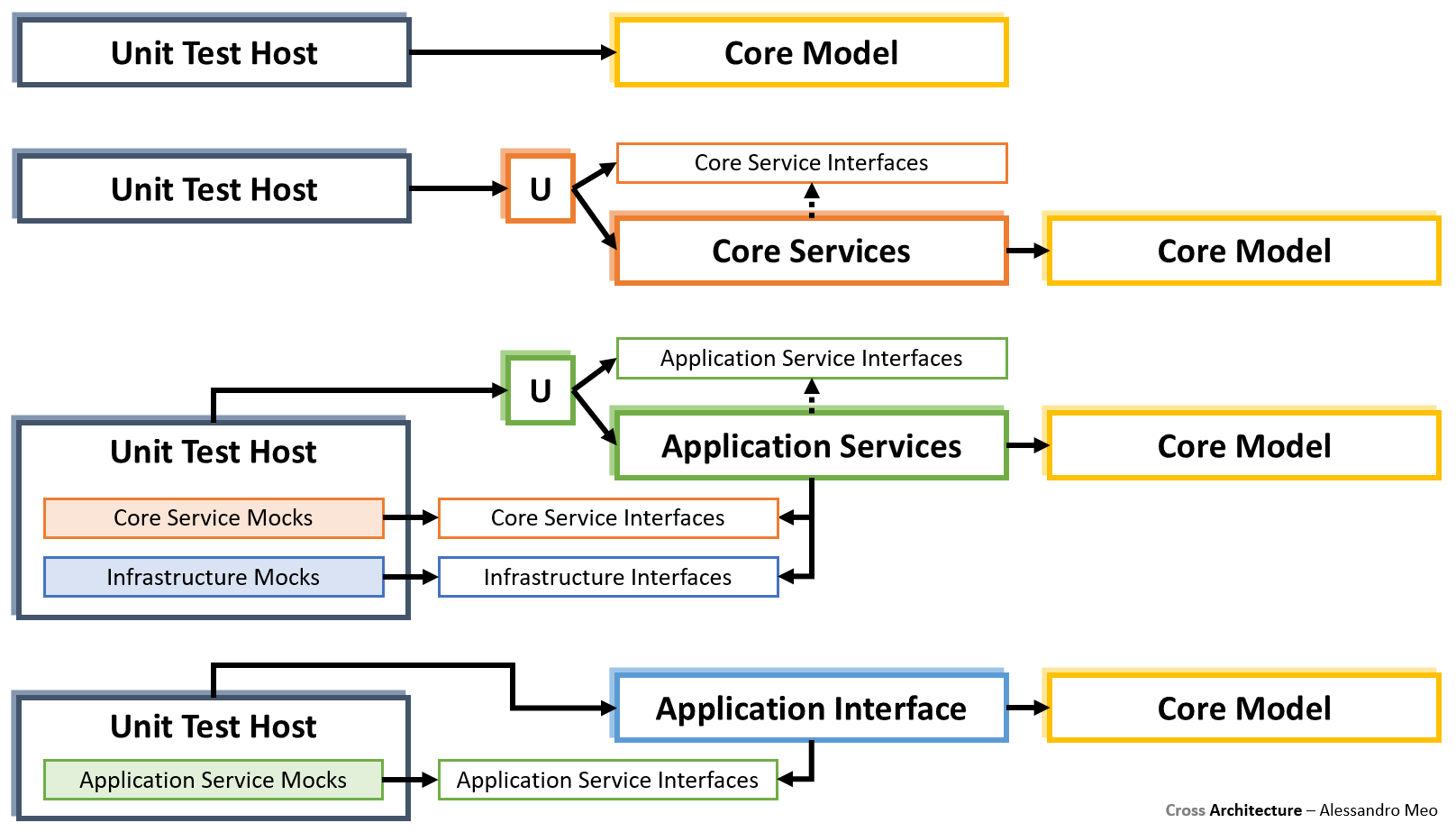

Leveraging the Composition Chain technique makes it possible to implement isolated automated test blocks, easily referencing any unit or group of layers without composition code duplication.

Some examples about are shown in the following sub-sections.

Unit Testing

The Cross Architecture provides several isolated testable units; each of them can be referenced by means of a single Unit Composition Ring (like the Core Services and the Application Services) or even directly (like the Core Model and the Application Interface).

By the above mentioned references, each part of the SW (not interacting with external systems) may be tested in isolation; anyway, writing tests for a particular SW block firstly requires considering if it may be worth doing.

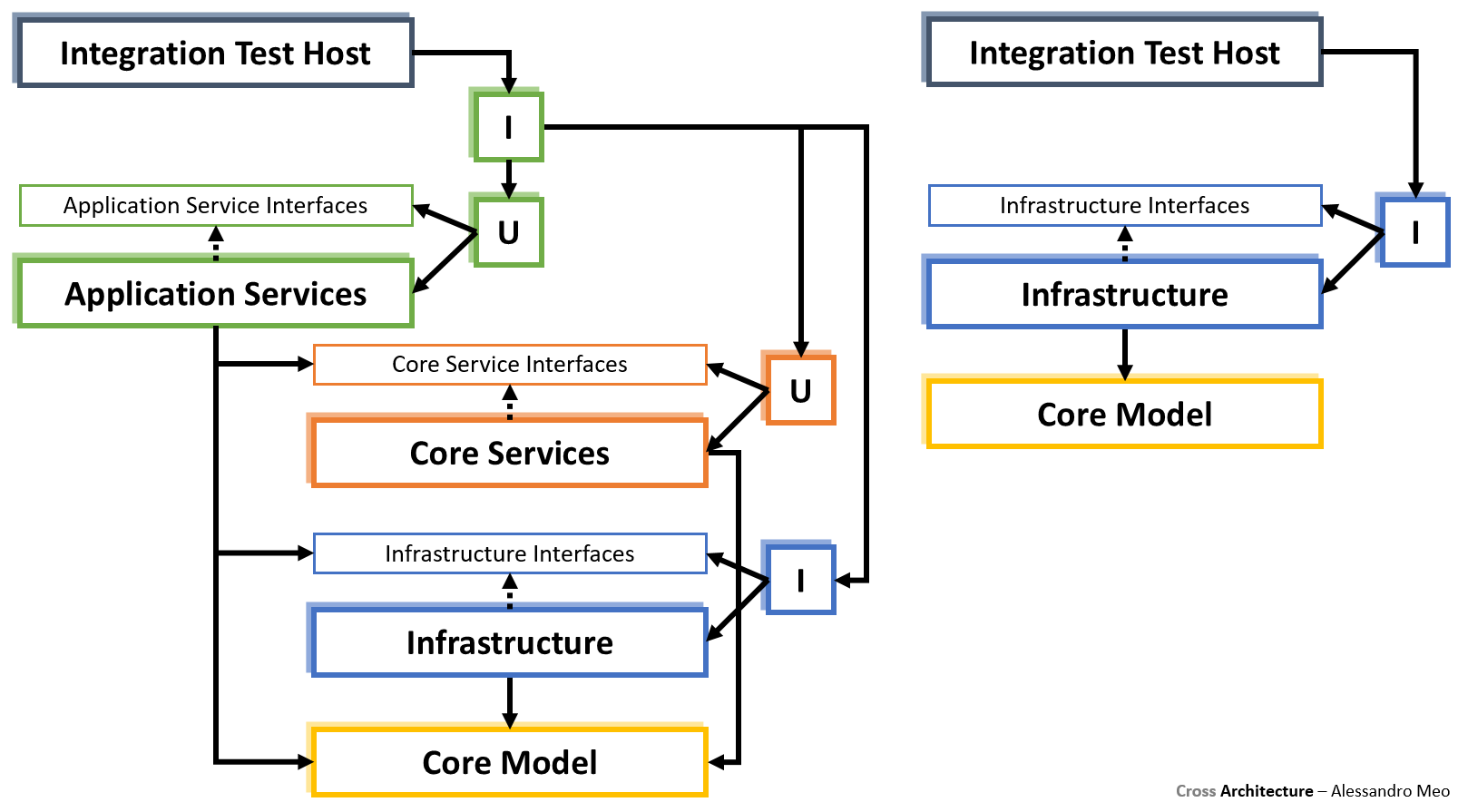

Integration Testing

Referencing a group of SW blocks for integration testing is much like doing that for test units; that’s the case of the Application Services integration testing, along with the SW blocks used by them, or the Infrastructure integration tests (where external systems get involved); in both cases only a single Integration Composition Ring is required to be referenced.

Functional Testing

Despite being logically different, functional tests can be structurally implemented as an overall type of integration tests; which means that the Functional Test Host only needs to reference the topmost Integration Composition Ring and the Application Interface.

Architecture Reduction

The most important aim of the Cross Architecture is to flexibly adapt to the actual application needs. This is done by the so called Architecture Reduction, which mainly implies:

- dividing a Logical Area into multiple SW blocks rather than implementing it as a single SW block;

- making the internal design of the SW blocks more or less complex;

- skipping the implementation of unrequired Logical Areas;

- duplicating the whole architecture schema when deep separation between sub-contexts is required.

The next sub-sections present some examples of Architecture Reduction for some of the most common scenarios.

DDD

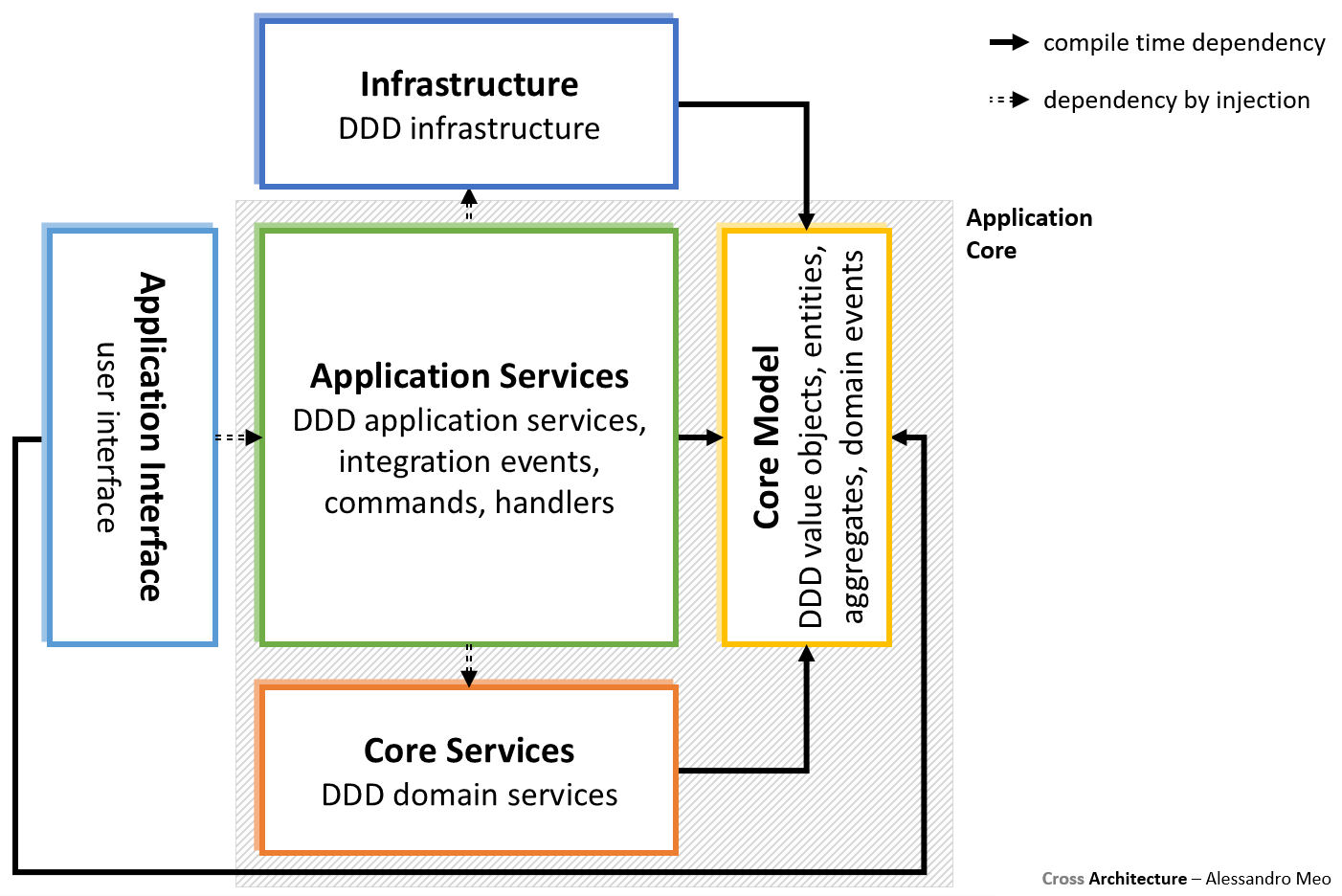

Implementing a DDD approach with the Cross Architecture leads to a design much similar to the one produced by the Onion Architecture, as highlighted by the Application Core logical area, which recalls one of its typical concepts.

On the other hand, with respect to the Onion Architecture, the Cross Architecture adds:

- constraints about the references between SW blocks; e.g.: the Application Interface can only interact with the Application Services and the Core Model, while the Core Services get “hidden” by the Application Services; this is different from the Onion Architecture where all the “inner” blocks can be referenced by the “outer” blocks;

- information about the injection points; e.g.: the Infrastructure get injected into the Application Services, but not into the Core Services; this enforces a pure “DDD style”, where the domain services are not allowed to interact with external systems;

- isolation of the interfaces into dedicated SW blocks, enabling two way decoupling between the interface referencer and the interface implementer.

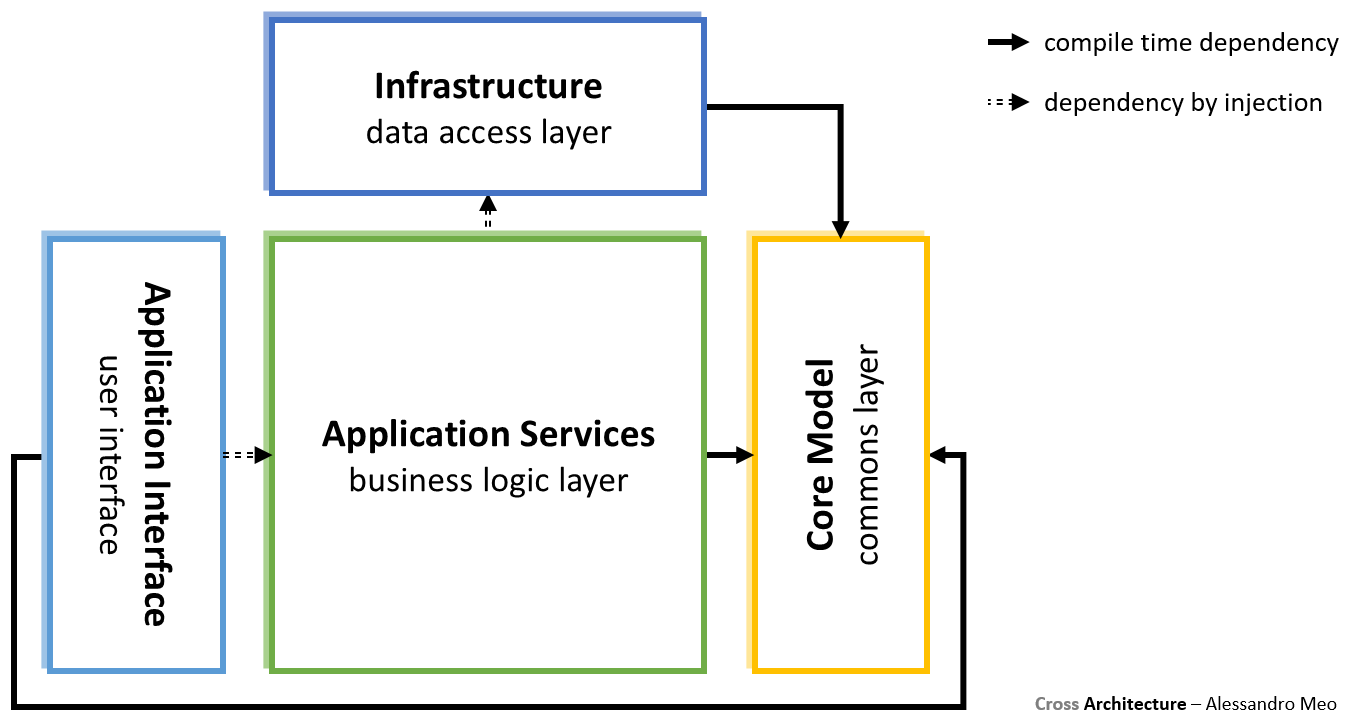

Multi-Layer

The “classical” multi-layer architecture, composed of the UI, BLL and DAL layers, can be easily implemented in Cross Architecture by mapping those layers to the Application Interface, Application Services and Infrastructure logical areas.

With respect to the “classical” multi-layer approach, the Cross Architecture adds loose decoupling between layers and a mandatory Core Model, gathering common elements, referenced by all the other layers, but also implementing the core of the application data model. The Core Model cannot be a bare collector of shared elements, but it should be considered as one of the main elements of the architecture when organizing concerns and distributing responsibilities.

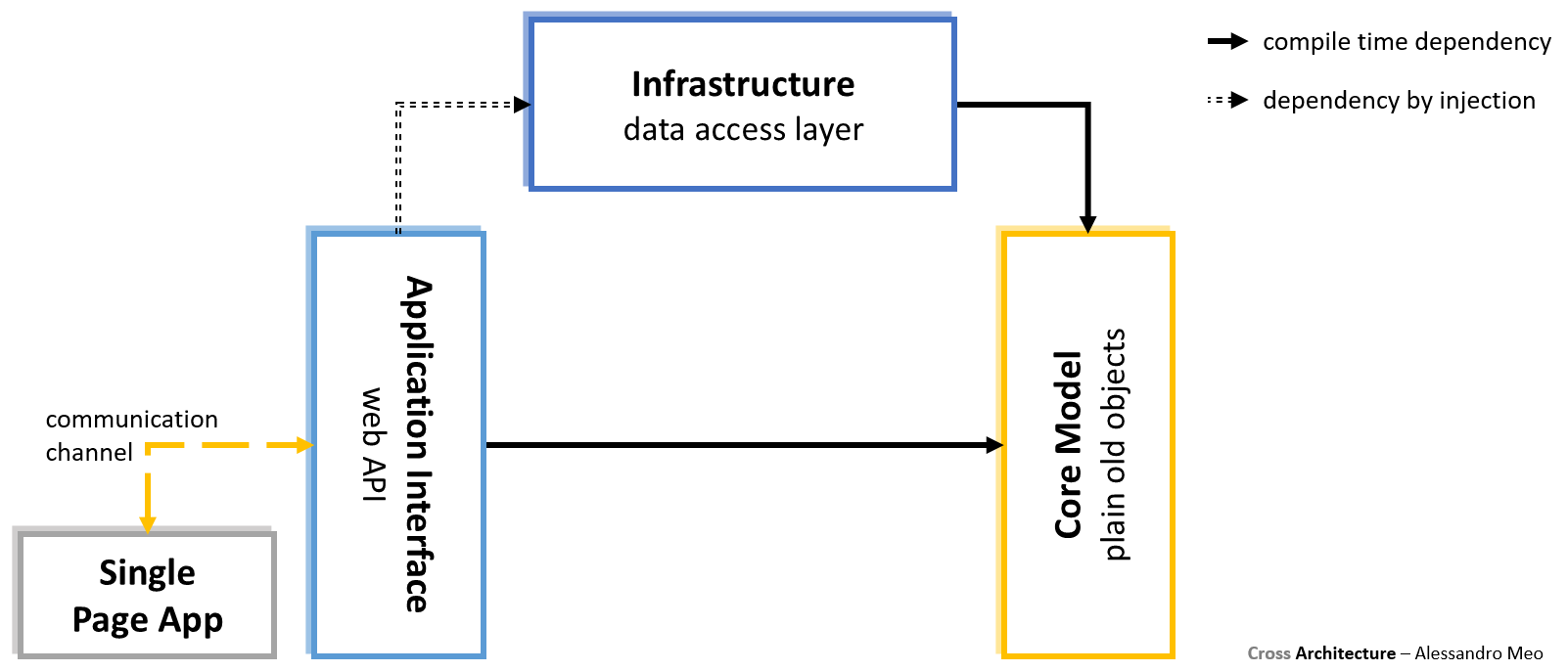

Simple CRUD

A simple CRUD application does not have a properly defined business logic, so it may be implemented removing the Application Services, which are defined as an optional Logical Area by the Cross Architecture; the resulting design is very dry and makes use of the optional reference between the Application Interface and the Infrastructure.

In the example above, the Application Interface is implemented by a web API application, eventually called by an SPA.; this is only to stress that, in the Cross Architecture the application interface is not necessarily dedicated to human users; moreover, the calling the SPA. was included in the schema only as an example, but it is not covered by the Cross Architecture.

Simple In-Memory

This example shows the simplest scenario covered by the Cross Architecture, where the Application Interface exposes an in-memory working logic, condensed into the Core Model.

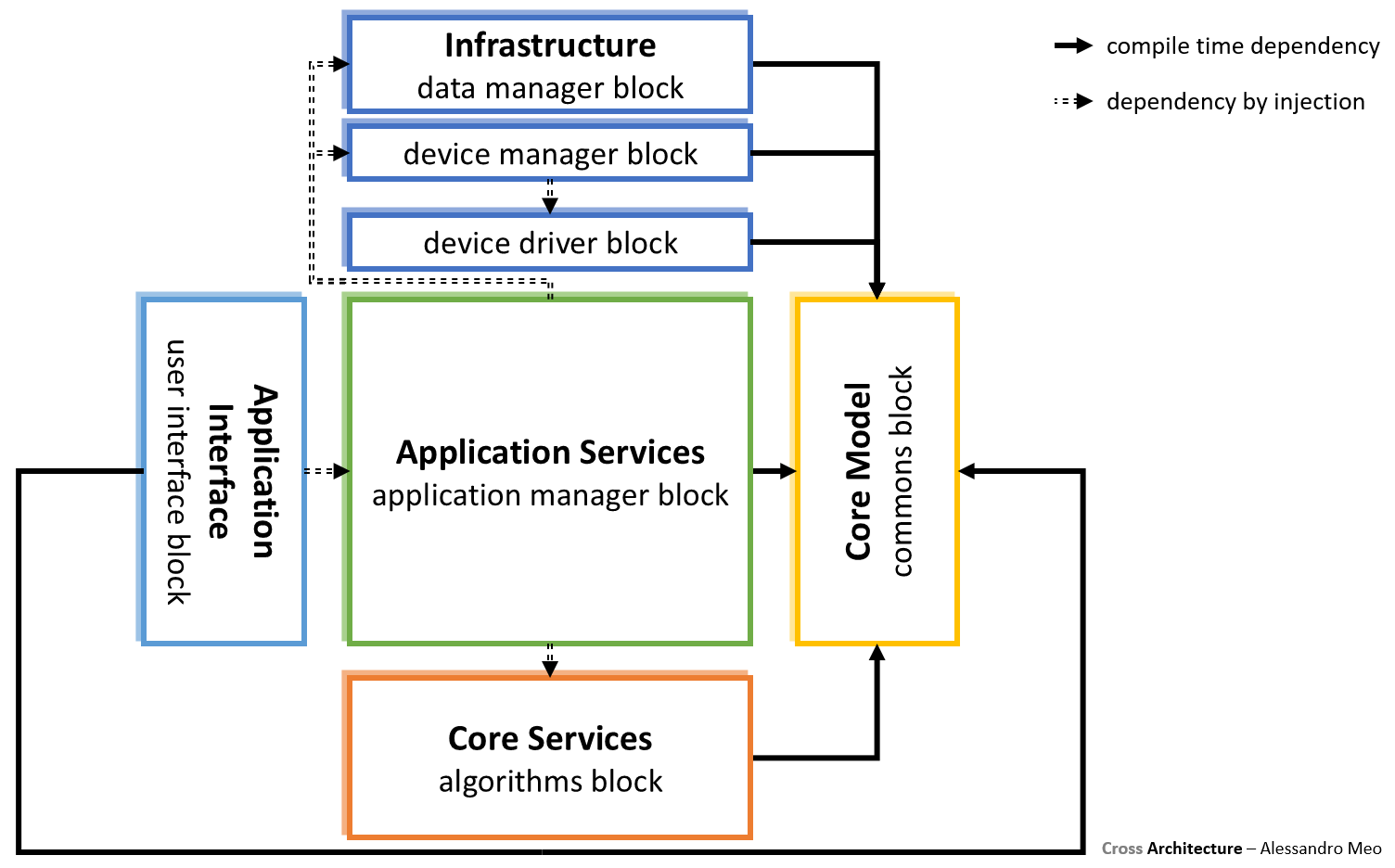

SW Built Around a HW Device

This example comes from one of the applications I’ve been working on during the last few years, which is a SW acquiring images from a custom HW device and elaborating them by means of some algorithms. The application was designed as a loosely coupled multi-layer software and, in particular, several layers were needed to abstract from the custom HW.

Reconsidering that architecture in order to fit into the Cross Architecture led to the schema above, where the Infrastructure has been split into several SW blocks for interacting with the database, on one hand, and with the custom HW, on the other hand. Also, the presence of multiple loosely coupled layers for interacting with the custom HW (the “device manager” and the “device driver” blocks) perfectly fits into the Cross Architecture philosophy.

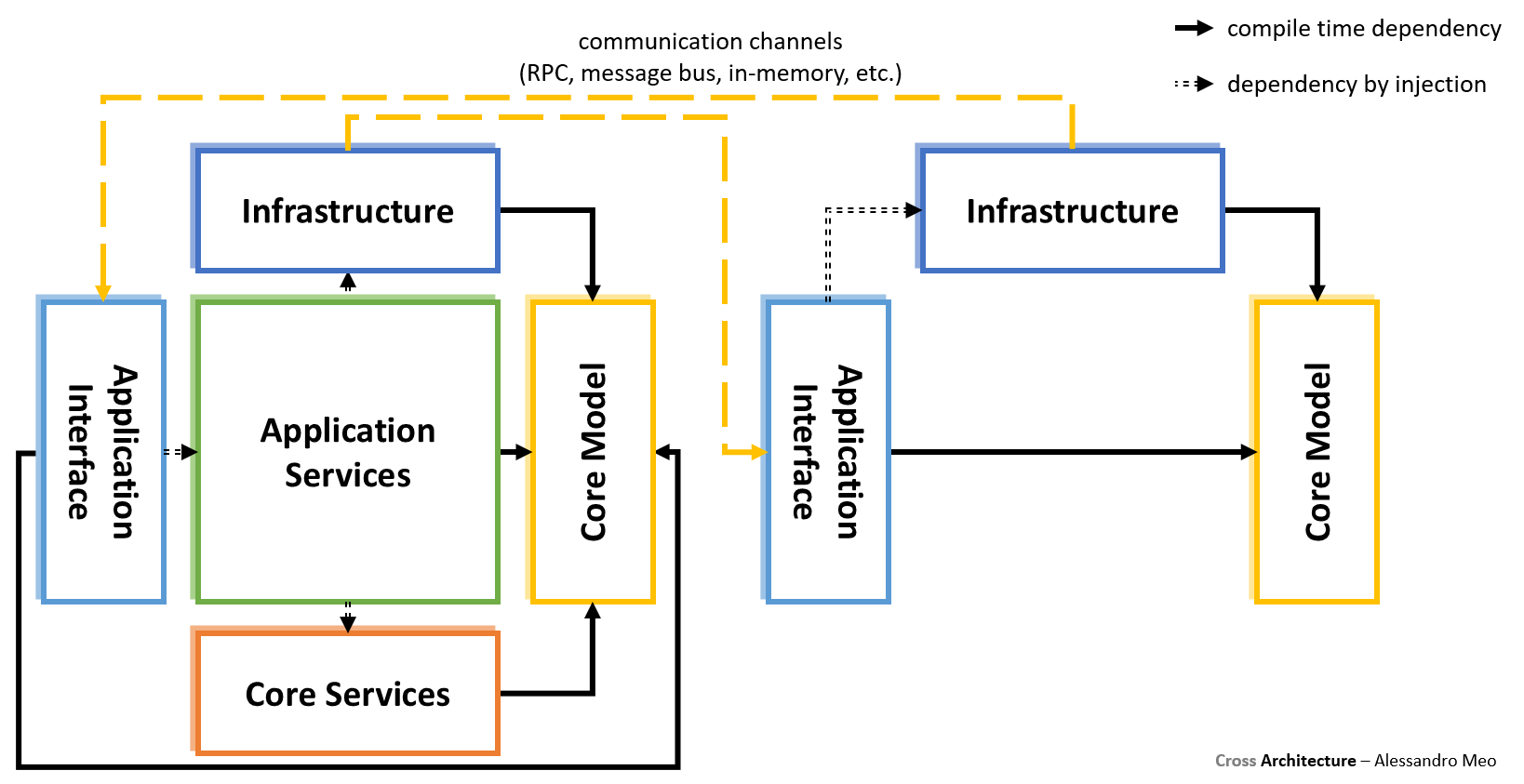

Micro-Services

As already stated, the Architecture Reduction includes the possibility to duplicate the whole architecture schema when deep separation between sub-contexts is required; this type of reduction is particularly suited for the micro-services scenario, as shown above (remarks: the displayed communication channel is only one of the possible interaction scenarios between micro-services; a complete description about is beyond the scope of this article).

In this case, the Cross Architecture helps in differentiating the internal design of the micro-services starting from their actual needs, while keeping their architectures tied to the same general schema and rules.